Dynamic pricing – or surge pricing, as it’s sometimes called – is where the price of a product or service changes depending on the demand that’s out there – and perhaps based on the supply that’s available too.

Say something normally costs €5 – but suddenly a lot of people go at the same time to buy it… when this happens a little algorithm automatically (and quietly) bumps the price up to €6 or €7… or maybe even €10.

You tend to see it where there’s a finite amount of supply – either because there’s a hard limit on the number of items available, or it’s a service that’s available during an in-demand timeframe.

The reckoning is that, with enough people looking to buy it, there’s bound to be enough that will pay an inflated price.

It's kind of like a perfectly distilled example of the laws of supply and demand, happening in real time; almost as if people are unwittingly getting involved in a bidding war.

Ideally, it should work the other way – if there’s no-one interested in that €5 product, maybe the price slips down to €4 or even €3. But generally what happens in the real world is that ‘dynamic pricing’ means prices go up, not down.

This sounds a lot like what happens when you’re looking to book a flight…

Yes – airlines have been doing this for years now; and we’re all familiar with the way prices work when booking a flight.

The price of a seat on an empty plane might be relatively low, but if you’re getting the last one left it’s going to be much, much more expensive. Even though what you’re getting is the exact same as what the first ticket-buyer got.

In fact dynamic pricing is fairly common in the travel and hospitality sector – because hotels often have a similar model for rooms.

The price of a room tends to be lower when there are lots available, but it goes up as bookings increase – and during periods of higher demand.

And these pricing models are getting more sophisticated all the time.

Taking airlines as an example, in the past there might have been a relatively crude model where prices got higher as you got closer to the day of the flight – but often there would be seats left that they’d then need to sell off on the cheap in order to fill the plane.

But last minute deals on flights aren’t really a thing anymore, because airlines have gotten better at using the data they have to predict demand, and what people will pay, so that they fill up the plane in plenty of time.

And it’s the fact that companies now have access to all of this data – and these complex algorithms – that explains why we’re now seeing dynamic pricing creep into so many other parts of our day to day lives.

Where else are we seeing this?

Uber is essentially a taxi app in Ireland – but officially it calls itself a ‘ride sharing platform’.

In the likes of the US and UK it allows pretty much anyone with a car to give people a lift to their destination in return for money.

And, in its early years at least, it gained a reputation as a far cheaper alternative to an official taxi driver – like the yellow cabs in New York.

But what was built into that seemingly cheaper pricing model was what it called ‘surge’ pricing. That’s their name for dynamic pricing.

So if you want an Uber on a mid-week afternoon, it will probably be fairly cheap… but if you want one during rush hour, it’s going to cost you a good bit more.

Uber’s argument is that it’s a way of managing demand – if you really need a lift at that moment, you pay more, if you can wait, then you should be able to see prices fall back to normal.

And most people accepted that – it was the price of using the platform.

But because this system is essentially automated by an algorithm, there were unforeseen consequences.

For example, people felt particularly aggrieved at Uber raising prices during bad weather events like snowstorm – as they felt like they were profiting from disaster.

But worse than that, there have been multiple occasions where prices jumped because people were scrambling to get out of a city centre due to a terrorist attacks and mass shootings.

Uber prices doubled in London in 2017 in the immediate wake of a terror attack at London Bridge.

Last year ten people were shot on a subway in Brooklyn, and prices on Uber – and its rival Lyft – jumped there too.

Uber has the ability to switch off surge pricing in these kinds of occasions and its policy is to do so during emergencies, natural disasters or other unusual market disruptions – but in the case of London, it was accused of taking too long to respond.

What about gigs…

Yes, Ticketmaster has also dabbled in dynamic pricing at some of its gigs in recent years.

Ticketmaster claims it’s an anti-tout measure - and it’s been used by some fairly big names too; Harry Styles and Coldplay in their recent tours, for example.

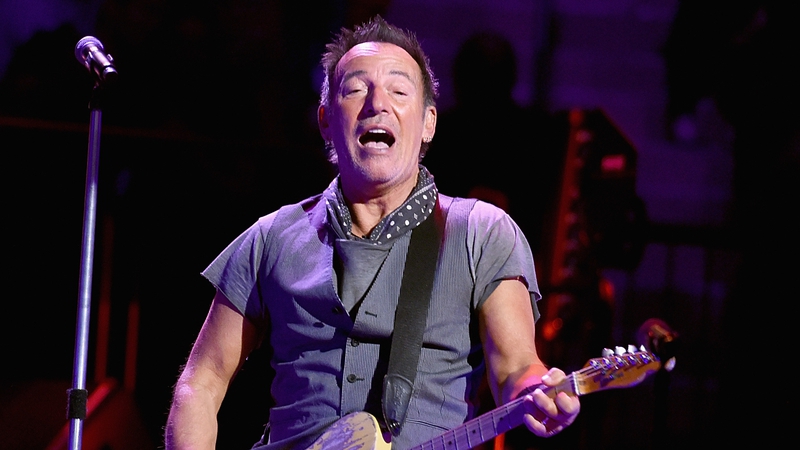

Not to mention man of the people, Bruce Springsteen.

He used dynamic pricing in some of his US dates last year – which led to a small number of tickets costing $5,000.

And of course he didn’t have to use the system – he could have chosen not to. But he actually defended doing so when asked about this by Rolling Stone.

His argument was that, for most of his career, he had aimed to sell tickets at slightly below the market average. But on this tour he decided that he and the band were getting old, and it was time to cash in and do what everyone else was doing.

(Which almost seems to imply the guys have been scraping a living up until now.)

Springsteen also argued that those silly prices for a gig ticket were happening long before he started using dynamic pricing – but it was ticket resellers or scalpers who profited, and not the people putting on the show.

He also said if anyone had any complaints on the way out of the show, they could have their money back… it’s not known if anyone took him up on that offer.

And now dynamic pricing is even making its way into pubs and restaurants…

Yes, a British pub group, Stonegate, recently announced it was going to add a 20p surcharge on the price of a pint during its busiest hours in the evenings and on weekends.

Stonegate operates around 800 venues around Britain, so it’s a pretty big group that will impact a lot of consumers.

They’ve called it ‘dynamic pricing’ – though their price change is fairly crude – it’s not actually responding to supply and demand in real time.

But the spirit of it is the same – and ultimately it means people will have to pay extra when it’s busy.

Could a pub here do something similar?

In theory, yes.

There are rules around pricing in pubs – but they’re more focused on cutting prices than raising them.

Pubs aren’t allowed to drop prices below what they were at the start of each day – that rule was brought in as a way of banning things like Happy Hour.

But there’s nothing to stop them raising prices at certain points of the day – so you could have a pub that adds 20c to the cost of a pint just in time for the post-work rush.

Or they could have higher prices on weekends compared to weekdays.

And there certainly would be cases of pubs and clubs that have a higher charge for drinks after a certain time.

But the reality is that most just set their price and leave it at that – because it’s the easiest way to operate.

And you can imagine it would get fairly frustrating for customers if, every time they went to the bar, they were charged a little bit more for a round.

But there’s a practical element too – because pubs are also required to display their prices clearly – so if they were going to introduce ‘dynamic’ pricing they’d have to be very clear about what was going to be charged at any one time.

The same applies for restaurants – they’re free to adjust prices however they want, but they need to have their price list clearly displayed both inside and outside of the premises.

So trying to keep that updated to reflect the current price would make it more hassle than it’s worth for most, I’d say.

Is there anything to stop other companies introducing dynamic pricing here?

Not really – again, the likes of retailers are free to set and change their prices.

The key rule, though, is that the price is clearly displayed to consumers so they know how much they’re paying before they get to the till. That way they can make an informed decision as to whether they want to buy it.

And it’s for that reason that dynamic pricing will largely be confined to digital services and online retailers – for the time being at least.

Because, to do it properly, you need a system that’s constantly monitoring demand and stock levels, and adjusting the price from one minute to the next.

Doing that in a physical shop is going to be very difficult – and annoying for customers. But it’s easier for the likes of Amazon – which might explain why you can get a very different price for an item from one day to the next.

But even the digital services already using dynamic pricing elsewhere may struggle to do so here.

Uber, for example, has pushed for their deregulated business model to be permitted here, but they’ve been told that that’s not going to happen.

That means that they’re reliant on licenced drivers – like taxi drivers – and what they can charge is set and regulated by the National Transport Authority.

There is a very crude type of dynamic pricing at play there – fares are a little higher between 8pm and 8am, there’s also a special premium rate that applies between Christmas Eve and St Stephen’s Day, and then New Years Eve and New Years Day.

But it’s nowhere near the kind of difference that we’d see with surge pricing on the likes of a Saturday night in the city centre, for example.

That’s one thing people can be grateful for when they’re struggling to get a taxi after their Christmas party – once they do get one, they’ll at least have a fair idea of what the cost will be.