Analysis: from the "black loaf" to a shortage of tea, the Emergency's hardships forced Ireland to try out many alternative foodstuffs

This article is now available above as a Brainstorm podcast. You can subscribe to the Brainstorm podcast through Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts .

By Bryce Evans, Liverpool Hope University

In the aftermath of the Munich Agreement of 1938, the British Board of Trade secretly decided that economic blockade tactics would be used in any coming conflict, even against neutrals. In time-honoured tradition, Britain would use hunger as a weapon of war against all. The goal? To force neutral shipping into British hands and neutral states to Britain's side.

The "phoney war" following Britain's declaration of war on Germany in September 1939 ended in June 1940 with the fall of France. British prime minister Winston Churchill made Taoiseach Éamon de Valera a deal: end neutrality and Britain would end partition. De Valera’s refusal prompted a bitter Churchill to respond by subjecting Ireland to a crippling supply squeeze.

Although diplomacy dominates popular understanding of the Emergency, the use of hunger as a weapon of war deserves much greater emphasis. When Churchill turned off the tap, Ireland’s agricultural economy, perilously reliant on British supplies, was devastated. In 1940, the State was importing six million tons of animal feed from Britain, but the figure was zero by 1942. It was the same with fertiliser: 74,000 tons in 1940, zero by 1942. Other vital modern productive aids, from pesticides to tractors, all but disappeared too.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's History Show, Bryce Evans on life in Ireland during the Second World War

Naturally enough, this meant that Irish food production was seriously hamstrung. Churchill's strangulation of independent Ireland’s economy combined with other factors – such as the country's inadequate merchant navy, wartime inflation and the late introduction of a full rationing system – to ensure that the majority of people in the state experienced what would today be termed food insecurity or food poverty.

Not that you would have known this from British propaganda of the day, which portrayed Ireland as a greedy neutral, implying that its inhabitants were the well-fed residents of a land of milk and honey. This portrayal of the abundance of the "other", in contrast to absence endured at home, was a staple of wartime food propaganda (it was deployed by Nazi propagandists to depict Jewish people as gluttonous).

Irish wartime propagandists resorted to the absence versus abundance narrative too. The reality of material deprivation was spun as evidence of the superior morality of Ireland's neutral stance. While the rapacious combatants went about their predatory and voracious conquest, the virtuous yet resolute Irish body would thin and harden.

But the absence versus abundance narrative would rebound on the Irish state in unwanted ways, exacerbating the rural/urban divide. Surveys revealed that a sizeable proportion of inner-city Dubliners had never eaten fruit or vegetables and there was a surge in childhood rickets. "The poor are like hunted rats looking for bread", remarked one TD of the city's food queues and seedy black market transactions. Some envious Dubliners imagined their rural counterparts growing plump off the fat of the land, an impression aggravated by a ruralist political culture which held aloft the "pure" agrarian smallholder.

A civil servant visiting a remote Gaeltacht area in 1942 recorded ghostly "half-starving people" begging for food, cursing Dublin and predicting famine

Of course, the reality was very different. Along with the feed and fertiliser, Churchill had cut the fuel supply and the resultant lack of transport hampered the distribution of food which was hardest felt in outlying rural areas. A senior Irish civil servant visiting a remote Gaeltacht area in 1942 recorded ghostly "half-starving people" begging for food, cursing Dublin and predicting famine.

As supplies of food ran low, Irish people turned to alternative foodstuffs. Ireland had the highest consumption of tea in the world at the time, with government research listing it as the "principle item of food" for the Irish poor. Its absence was therefore keenly felt and wacky and unpalatable substitutes duly appeared. From the many colourful prosecutions of the Emergency period, the fining of one female shopkeeper for selling watered-down turf mould as tea stands out.

The government's hated "black loaf" was trumpeted as more nutritious by health officials. In fact, the 100% wholegrain bread, introduced to conserve wheat supplies, caused nutritional deficiency and was roundly detested. Many turned to poaching and hunting, with more rabbit meat consumed and even reports of Dublin Zoo's carnivora falling victim to hungry citizens.

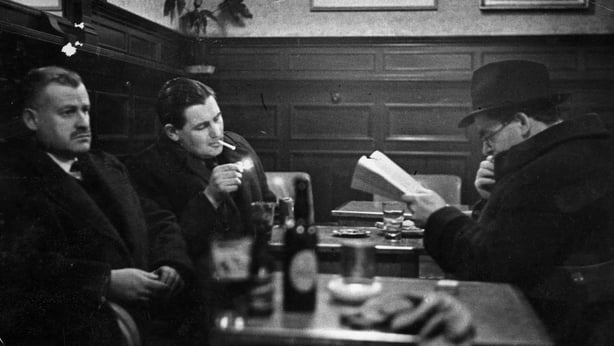

The black market boomed. While this was denounced as immoral by leaders of church and state alike, evidence suggests that most people dabbled in black market exchanges. Many did so while simultaneously excusing themselves by decrying the "real black market" and the familiar bogeymen operating it,the "large-scale racketeer", the "middleman", the "gombeen men". As one eminent theologian reasoned while justifying procuring a small amount of tea on the black market in a heated debate on pricing in the pages of the normally sedate Irish Ecclesiastical Record, "there's nothing like a nice cup of tea".

This sort of attitude infuriated members of the rather straight-laced bureaucracy charged by the government with enforcing state regulations. Armed with the moral economic imperative of preventing starvation, a bloated inspectorate doggedly pursued harsh prosecutions against small farmers who weren’t producing enough food and small traders who were overcharging for it.

However, the state's admirable imperative of ensuring fair shares in food was undermined by structural problems. The belated introduction of a full rationing system resulting in the bafflingly frequent revision of price orders. While the true extent of the British supply squeeze was hidden from the public, it did mean that the government was pressuring farmers to produce ever more food, despite the fact that they simply did not have the productive aids to enable them to do so.

The black market was further aggravated by another structural obstacle (the very same one which had informed Churchill’s squeeze in the first place): partition. Smuggling boomed across the porous frontier between Northern Ireland and Ireland, launching a thousand smuggling yarns. This enabled people north and south to supplement food supplies, but it also undermined rationing systems in both territories.

Ultimately, in appraising the Irish government’s record on food management during the Emergency, it is notable that there were no cases of death with starvation as a principle cause so the state clearly fulfilled a fundamental humane duty. On the other hand, though, many people in this period were still opting to swap hunger pangs for the promise presented by emigration.

Dr Bryce Evans is Associate Professor in History at Liverpool Hope University

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ