In ancient Ireland and beyond, women were buried with objects that suggest the dead women had been held in high regard by their communities as ritualists, shamans or priestesses. In this extract from his fascinating new book Pagan Ireland: Ritual And Belief In Another World, John Waddell explains what can these graves tell us a lot about the status of the "bean feasa

Women ritualists may have been common throughout prehistory. They are represented in a few important prehistoric burials that may be considered unusual in one way or another. These women probably prefigure the 'wise women’ or ‘women of knowledge’, mná feasa, of traditional Scottish and Irish folklore. The special gifts of the bean feasa included second sight, prophetic capabilities and healing powers.

However, one burial, dated to AD 420–540, was particularly interesting. This was of an elderly woman, over 60 years of age, an exceptional age for a woman at that time. She had suffered from post-menopausal osteoporosis of the spine, resulting in severe spinal curvature. Strontium and oxygen isotope analysis indicated that she was of local origin and, as Elizabeth O’Brien, in her magisterial study of Iron Age and medieval burials and burial practice observes, she must have been of high standing in the community, who would have cared for her for some time in her later years. Elevated rank may not, however, have been her only or most important quality. Her disability provides a clue to her special status—she may well have been a ritualist, a bean feasa, with special powers.

In another case, in 1903, a small burial mound was investigated in the townland of Farta, near Loughrea, Co. Galway (the name being an Anglicisation of the Irish fert, ‘burial mound’). It had been built to contain a Bronze Age cordoned urn and a cremation inverted on a stone slab and dating from about 1500 BC. Over 1,000 years later, the extended body of a woman aged 20–25 years was inserted into the older monument. She was accompanied by some pieces of deer antler and a seven-year-old stallion, laid on its left side. Strontium and oxygen isotope analysis suggests that the woman was not of local origin but had spent her formative years in eastern Ireland or eastern England. Interestingly, she had an inward twisting of the knee or in-toeing, and this would have given her an abnormal gait.

Animal sacrifice

This woman’s remains were radiocarbon-dated to AD 383–536, the horse to AD 388–536, and thus they are contemporary. We do not know how the horse died but, since it and the woman are unlikely to have expired simultaneously, horse sacrifice is a distinct possibility. Horse burial is exceptionally rare and implies that this was a prestigious interment.

Interestingly, the deer antler was dated to AD 564–677 and was presumably introduced one if not two centuries later, when the significance of this prestigious burial was evidently still remembered. Again, it seems probable that the woman’s physical impairment may have afforded her a special status. The deer antler was a significant addition, because antlers are associated with shaman rituals elsewhere and might be an allusion to this woman’s special powers. O’Brien notes antler deposits in several other female burials of medieval date and suggests that they may have been symbols of regeneration and fertility.

No return to the land of the living

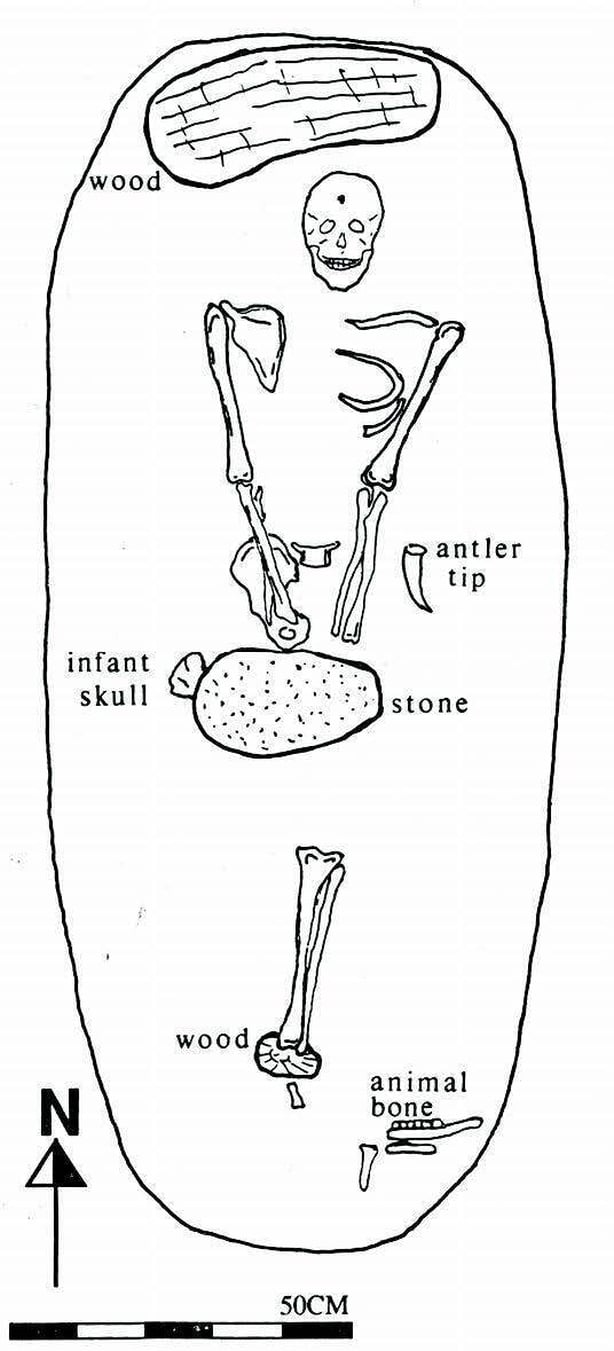

Also in the west of Ireland, another antler tine was found in another female burial, this time in a bog at Derrymaquirke, near Boyle, Co. Roscommon. The partial remains of an adult woman were found lying in an extended position with her head to the west. There was a large piece of wood behind her head and a large stone lying on top of her lower body. Some bones of a child, a small piece of antler, some animal bone and a small piece of wood were also found in the grave. The animal bone has been dated to 660–240 BC.

The atypical rite of unburnt burial at a time when cremation was the norm, the presence of animal bones (sheep or goat and dog) and the piece of deer antler all imply that this woman was of special significance. The burial in a bog and the placing of a stone on top of the corpse were perhaps meant to inhibit her return to the land of the living.

International parallels

Such unusual female burials are paralleled elsewhere in the world too, and perhaps provide us with a new interpretation of these ancient Irish burials. One remarkable discovery in Iron Age Burgundy sees the grave of the celebrated ‘princess of Vix’, who was buried with all the symbols of superior rank of the fifth century BC. Her timber tomb contained a four-wheeled wagon, rich personal ornaments and a drinking set that included an immense bronze wine vessel capable of holding nearly 1,100 litres and made in a Greek colony in southern Italy.

She was not physically distinguished, being of small stature (about 5ft in height), and she was marked by asymmetrical facial features and hip dysplasia that may have impaired her walking. These puzzling details and the quite outstanding nature of the grave-goods have all prompted the proposition that she was a high-status priestess or ritualist with some ceremonial role rather than a mere secular princess.

Another notable female burial, this time from Juellinge on the Danish island of Lolland, was also accompanied by rich grave-goods that included a bronze cauldron, a ladle, a wine-strainer, two glass beakers and two drinking horns. This woman lived around AD 100 and she too was lame, having a deformity of her right leg caused by an osteochondroma, a large benign tumour on her thigh bone. Both of these women may have had an important role in the sacramental serving of drink, and it may be more than a coincidence that both were physically impaired.

Though widely separated in time and space, many of these women clearly shared the distinction of being disabled in one way or another. And while the Galway woman was buried with a horse and no other prestigious goods, from this ancient cultural context, we can interpret that she may have been just as important in her own community in the west of Ireland as the wealthy ‘princess’ in eastern France all those centuries before.

John Waddell, formerly Professor of Archaeology in the University of Galway, has written extensively on Irish archaeology. His work on Rathcroghan, a place rich in myth and legend, inspired his interest in Celtic mythology and publications like Foundation Myths: the beginnings of Irish archaeology (2005) and The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland (2022) have been published by Wordwell.

This extract is from his latest publication, Pagan Ireland: Ritual And Belief In Another World (Wordwell Books) is available now on wordwellbooks.com and in all good bookshops.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ