For centuries, surgery was viewed as a last resort - and surgeons, with their hacksaws and blades, were held in low esteem. But as time went by, these skilled medical craftsmen began to insist on being taken seriously. In these two short extracts from Every Branch of the Healing Art: A History of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dr Ronan Kelly explains the origins of what we call surgery - and tells how Irish surgeons declared their independence

Surgeons versus Barbers: the origins of modern surgical medicine

Surgery as a profession is defined by its ‘authority to cure by means of bodily invasion’. As a practice, there is evidence of rudimentary procedures – such as trepanation – going back to Neolithic times. Any regulation of the practice, however, comes much later. By the Middle Ages, most medical ‘treatment’ in Europe took place under religious auspices, usually at a monastery (‘treatment’ perhaps overstates what was essentially symptom control and a preparation for death, illness and disease being considered just rewards for sin).

Two papal edicts – in 1163 and 1215 – forbade clergy from coming in contact with blood and other bodily fluids, after which they confined themselves to the more intellectual, book-based aspects of healing. Responsibility for bloodletting – by far the favourite response to just about any ailment – and other minor procedures devolved to the barbitonsores, those lay servants who already wielded sharp instruments for taking care of the monks’ tonsures.

Division of medical labour

This division of medical labour fostered an already-evolving distinction between medicine, also known as physic (hence ‘physicians’) – and surgery, also known as chirurgerie (etymologically, the word comes from the union of ‘hand’ and ‘work’ in ancient Greek).

As secularisation continued, the study of medicine found a new home in the early universities at Montpellier, Bologna, Paris, Oxford, Cambridge and elsewhere. In Ireland, the sole university, Trinity College, Dublin (established 1592), opened its ‘School of Physic’ in 1711. Physicians, then, were learned, literate, obtained medical degrees and called themselves ‘doctors’; it was not until the nineteenth century that they even used any instruments in making their diagnoses.

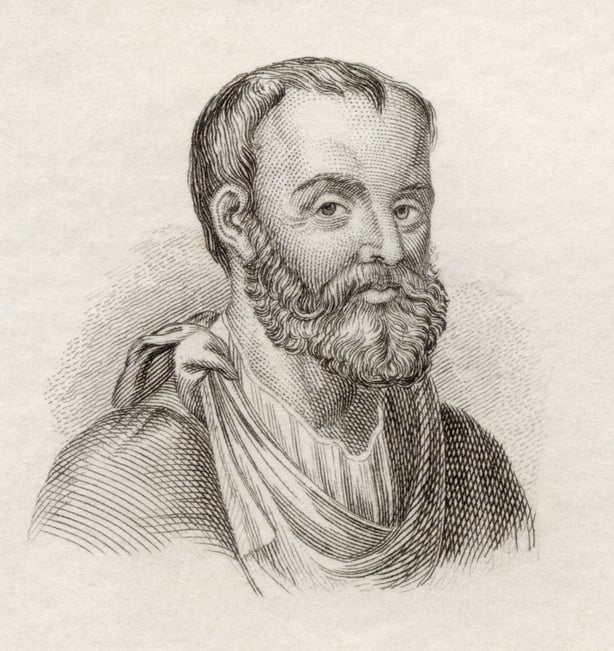

The "wisdom" of Galen

Unfortunately for their patients, their diagnoses were largely based on the second-century teachings of Galen (CE 129– c.216). In his theory, human health depended on an internal balance of four fluids, or humours: blood, phlegm, and black and yellow bile. The physician’s task was to interpret external signs – fevers, rashes, spots, diarrhoea – and prescribe a cure. More often than not, this was bloodletting (for which, call the barber-surgeon).

Alternatively, he might prescribe the ingestion or application of herbs, purgatives or emetics (for which he sent the patient to the third branch of medieval healthcare, the apothecary). For a millennium and half, until the Renaissance, Western medicine hardly moved on from Galen’s theories. Nor did it question his anatomical teachings, which were based on his dissection of cattle, sheep, pigs, goats – even elephants – but not human corpses, which was entirely taboo. In general, physicians did not (physically) intervene into the fabric of the body.

Rightly or wrongly, then, medicine enjoyed high status in medieval Europe. Surgical practice, meanwhile, as it spread beyond the monastic setting, endeared itself to few. Only when a patient had exhausted the expertise of their physician (or, for the poor, the local wise woman or folk healer) was surgical intervention contemplated. The practice inevitably meant pain, sometimes to excruciating degrees; operations had to be performed fast, often mercilessly; and anaesthesia, needless to say, was non-existent, though both patient and surgeon might swig something high-proof to steady nerves and lessen the horror.

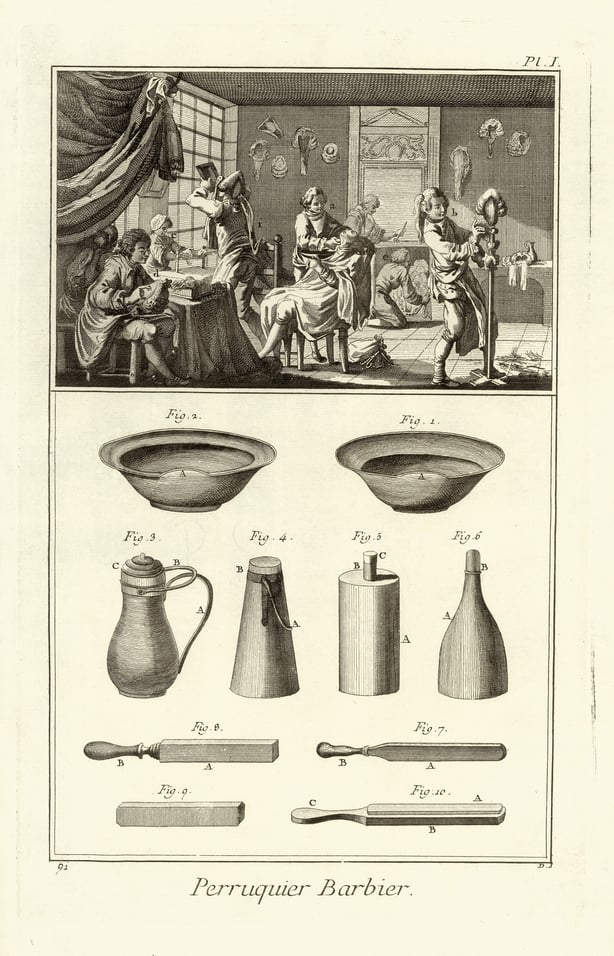

Lancing an abscess and shaving a beard

Some operators were better than others, but there was little meaningful distinction between a barber and a surgeon; with the necessary sharp blade, one could lance an abscess as easily as shave a beard. As guilds evolved as units of medieval civic society, the hybrid barber-surgeons were considered as one. For the benefit of their largely illiterate customers, they placed a sign above their door: the helical red-and-white pole still familiar in barbershops today (the occasional addition of a blue stripe is a much later American invention). Red and white remain the colours of RCSI’s livery.

The surgeons were further separated from the physicians by the range of instruments they carried: saws, knives, hooks, needles and lancets. Having such tools of the trade identified surgeons as practical, hands-on craftsmen. And like other craftsmen – blacksmiths, say, or coopers or tailors – aspirant surgeons were trained by apprenticeship. Training began at age 13 or 14 and lasted about seven to nine years. How competent anyone turned out was a case-by-case affair, entirely dependent on the master’s diligence – or lack thereof. (As far as guilds were concerned, regulation was largely about protecting their exclusive rights and prosecuting outsiders, as opposed to overseeing its members.)

The Guild of Barber-Surgeons: a Declaration of Independence

Dublin has the distinction of being the home of the oldest royally decreed professional body for surgery in these islands. On 18 October 1446, Henry VI established the city's Guild of Barber-Surgeons – ahead of similar corporations in London (1462), Edinburgh (1505) and Glasgow (1599). At this time, religious and civic matters were intertwined, and each guild, or fraternity, was named for its patron saint.

The barber-surgeons of Dublin thus constituted the Guild of St Mary Magdalene, and their associated chapel was in Christ Church Cathedral. A second charter, granted by Elizabeth I, copper-fastened the connection in 1577.

A dubious honour

For the founders of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI), however, this distinction of longevity was a dubious honour. The union of barbers and surgeons proved an uneasy one, especially for the surgeons, who were outnumbered – sometimes by as many as ten to one – by their barber brethren. For the best part of 330-plus years, then, whenever the surgeons attempted to reform their practice and institute meaningful standards, they were simply outvoted. Insult was added to injury in 1687, when a third charter expanded the guild to include apothecaries and periwig-makers.

At various points, the surgeons of Dublin attempted to extricate themselves from the guild – as their counterparts in Edinburgh and London had managed to do, in 1722 and 1745, respectively – but each attempt was thwarted.

Revolution!

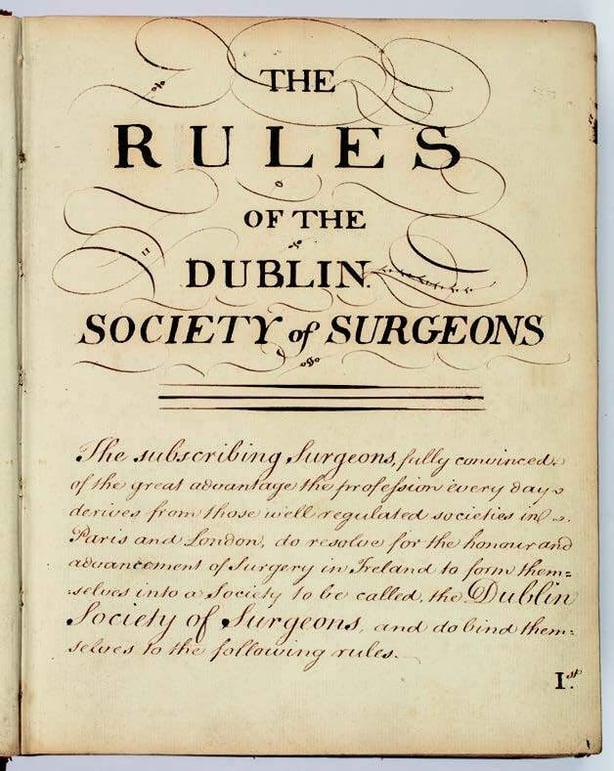

Until, that is, the year 1780, when a group who called themselves the Dublin Society of Surgeons began meeting twice a month – always on a Thursday – in various taverns in the city centre. In a revolutionary era – four years earlier, in 1776, the United States had declared its independence from Britain, while in France, the Bastille would be stormed before the decade was out, ushering in a secular state – these individuals were determined to start a revolution.

The minute book of these meetings – now in RCSI Heritage Collections – records that in the King's Arms, Fownes Street, they agreed to the following resolution:

That it is the opinion of this Committee that a Royal Charter, dissolving the proposterous [sic] and disgraceful union of the Surgeons of Dublin with the Barbers, and incorporating them seperately [sic] and distinctly upon liberal, and scientific principles would highly contribute not only to their own Emolument and the advancement of the profession in Ireland but to the good of Society in general by cultivating and diffusing, surgical knowledge.

In effect, the Dublin surgeons were making their own declaration of independence, both from the barbers’ dominance and from all religious influence. Indeed, even as RCSI has shapeshifted over the ensuing two and a half centuries, these originary ideals – administrative independence and a secular ethos – have endured as constants. How long the Dublin Society of Surgeons continued to meet is not known: there are no entries in the minute book after 3 May 1781 (by which time fines were being discussed for non-attendance, and the occasional meeting was adjourned for lack of a quorum).

A new petition

In any case, the major work had been done: the surgeons collected subscriptions to meet the expense of procuring a charter, and they engaged an agent to liaise with the Attorney General. Referring in particular to the precedent in London ('whereof the profession of surgery has been highly cultivated and improved’), their petition to the Lord Lieutenant reads in part:

…your petitioners humbly conceive that a similar regulation in this kingdom would be a means of further improving the science of surgery, and of great advantage to the public. Your petitioners therefore humbly pray your Excellency to recommend to His Majesty, that His Majesty may be graciously pleased to grant his royal letters patent, under the great seal of this kingdom, for dissolving and vacating the union and incorporation of the barbers and surgeons by the said charter of Queen Elizabeth, and for making your petitioners, and such others as may hereafter be elected members, a separate and distinct corporation, by the style and title of 'The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland;’ with such powers and authorities, and under such regulations, as are contained in the annexed draft (which is humbly submitted), or in such manner as to His Majesty in his great wisdom shall seem meet.

Now all they could do was wait.

Dr Ronan Kelly works in RCSI Library’s Heritage Collections. His book, Every Branch of the Healing Art: A History of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland is out now and available on wordwellbooks.com and in all good bookshops.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ