By Dr Paul Bolger and Madeline Hutchins, UCC

Over 200 years ago on the shores of West Cork, a young woman was avidly collecting, studying and identifying plants. Her name was Ellen Hutchins and she was Ireland’s first female botanist. Ellen Hutchins' name had been almost lost to history but in the field of botany her contribution is widely understood and hugely appreciated.

Born in 1785, Ellen’s story is a remarkable one. In a relatively short life, she made a significant contribution to the understanding of seaweeds, lichens, mosses and liverworts and produced the first flora of West Cork. She was highly regarded as an observer and collector of non-flowering plants by those botanists who described and published her finds, many of whom named plants after her in recognition of her scientific achievements.

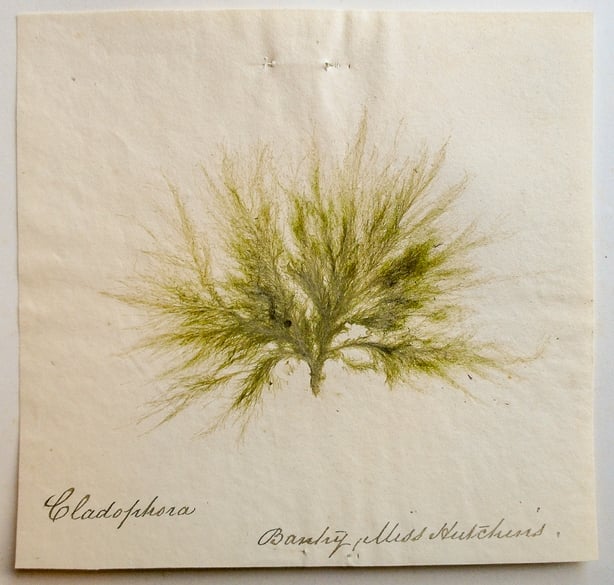

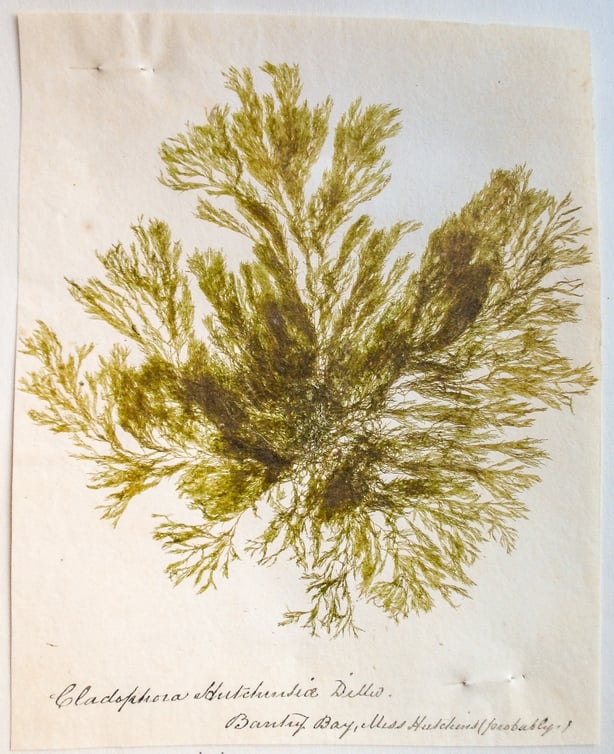

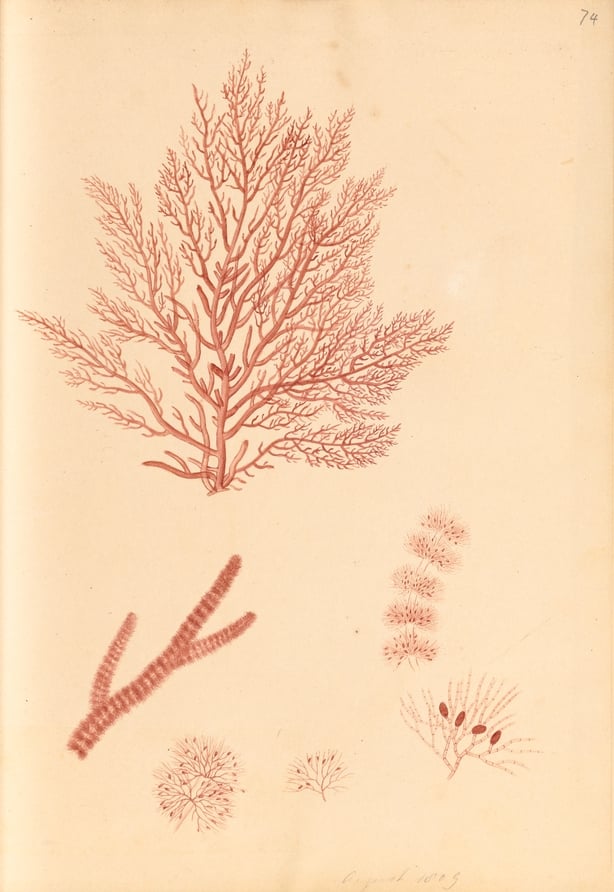

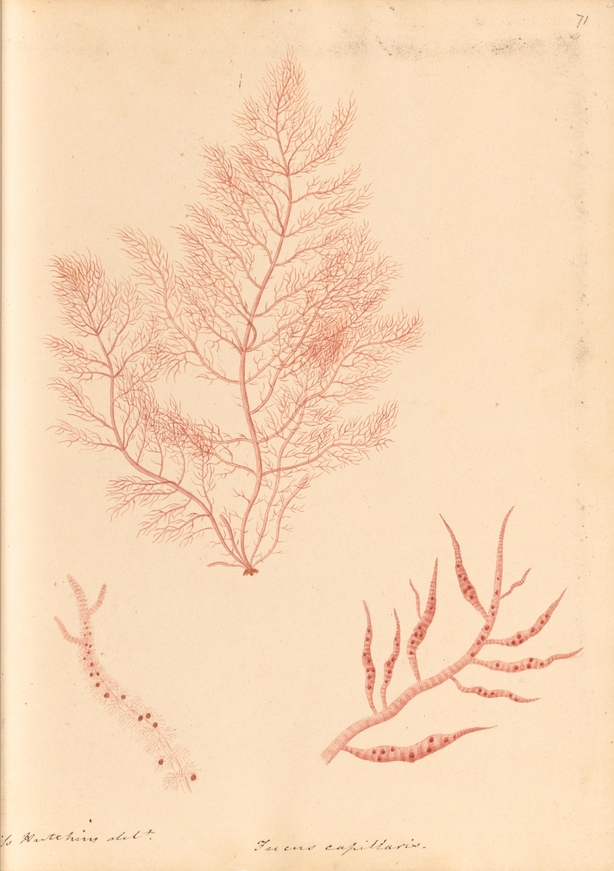

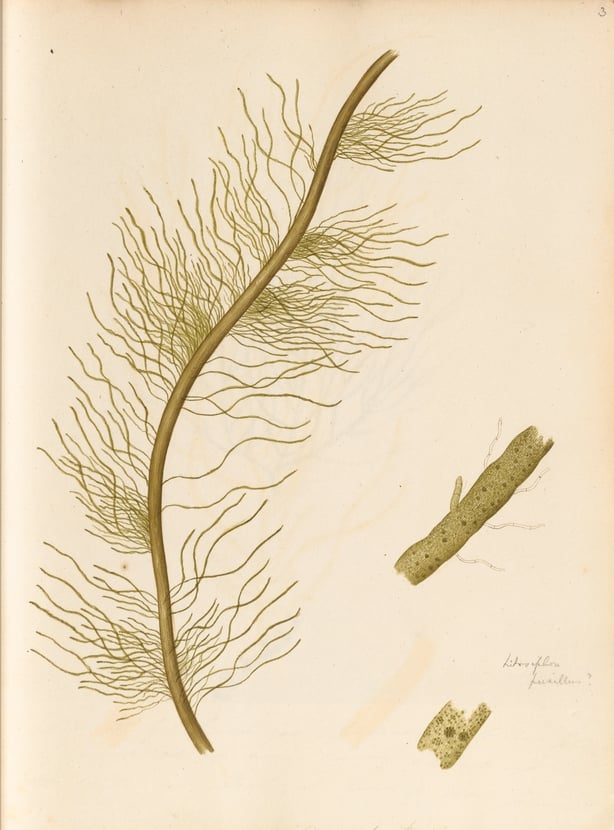

She was also a talented botanical artist producing many detailed and accurate watercolours of seaweeds which were crucial for conveying knowledge to other botanists. At Ballylickey, on the shores of Bantry Bay, west Cork, Ellen lived a lonely and restricted life, caring for her ailing widowed mother and a disabled brother. She also suffered from ill health herself.

Ellen Hutchins displayed many of the characteristics and core values which we consider essential for a successful researcher in the 21st century. A 2016 study in the scientific journal Nature identified the most important and highly regarded values and character traits among scientists; these traits include honesty, curiosity, perseverance, objectivity, courage, collaborativeness, and attentiveness. Ellen exhibited many if not all of these values through her short life’s work.

Curious and attentive

A key trait of the scientific researcher is the capability to notice the extraordinary amongst the ordinary. In Ellen's time, the early 1800s, the remote and as yet unexplored habitats of inner Bantry Bay offered a botanical treasure trove. The area had a magnificent wealth and diversity of plant life because of its mild climate and wide range of habitats, including ocean, mountains, woodlands, heath and bog.

Within this richness of nature, Ellen chose to specialise in a "curious and difficult" branch of botany, that of non-flowering plants. These plants were of minor interest to other botanists which allowed Ellen to establish her niche and create a legacy of discovery in relation to mosses, seaweeds and lichens.

With an innate curiosity about, and love for, the natural world outside her doorstep, Ellen applied herself with passion to the task of finding new species, sending carefully prepared specimens, detailed drawings and precise notes to fellow botanists. She was scrupulous in choosing typical samples, often selecting from hundreds of plants. In this, and in her noting of minute details to be certain of identification, she was the epitome of a meticulous researcher.

We need your consent to load this comcast-player contentWe use comcast-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTE Nationwide, Anne Cassin visits the Ellen Hutchins Festival in Bantry, Co Cork

Patience, courage and perseverance

It is hard for us to imagine what scientific fieldwork for Ellen was like. Hampered by social conventions and long skirts, and without modern day waterproofs and technology, she nonetheless ascended the local mountain summits - Knockboy, Hungry Hill and Sugarloaf. She wrote of setting out "at 3 o’clock in the morning" and "near breaking my bones yesterday on a mountain cliff seeking Jungermanniae [liverworts]" and another time "I rather crept than walked....as the ascent was so steep I could hardly stand upright".

On the seashore, she clambered over rocks with her boxes and baskets to collect seaweed specimens, and would return daily if necessary to a particular plant "watching its advancement to get perfect fruit". Back home in Ballylickey House she would have needed to preserve the plants quickly and painstakingly identify very small differences between species whilst they were fresh and unspoiled.

Ellen also showed perseverance and courage in continuing her botanical research when her health was poor and her caring responsibilities were all-consuming. In her social setting, she was doubtless seen as unusual and strange in pursuing a scientific study. She wrote "with me botany has been a solitary amusement" as there was no-one nearby who shared or understood her interest.

Joy of collaboration

The difficulty and solitude of Ellen’s scientific work was more than compensated by her sense of pleasure and enjoyment in sharing knowledge and discoveries with the community of specialist botanists in Ireland and UK studying the non-flowering plants. She had a remarkable collaboration, and built an incredibly strong friendship, with Dawson Turner, in Yarmouth, England.

They never met, but they corresponded and exchanged specimens over a period of seven years lasting right up to Ellen’s early death aged twenty nine. Turner's tributes to Ellen include "her pleasure in communicating knowledge, and her delight in being useful" and "the extraordinary talents and no less extraordinary industry which she displays in the pursuit of Natural History."

Lady luck

Serendipity has played more than a walk-on role in many great scientific discoveries. We think of Watson and Crick having providential access to Rosalyn Franklin’s crystallographic images of DNA, or the discovery of penicillin from Alexander Fleming’s orange mould. Ellen was in the right place at the right time to find many new species and play a significant part in increasing understanding of the non-flowering plants.

She was fortunate to live beside "perhaps the best garden in the world for the marine algae", she lived in a time of immense interest in plant-hunting and discovery, and she was fortuitously introduced to people in eminent positions with a willingness to support her, recognise her abilities and celebrate her successes. This seems to have been without prejudice or judgment about her age, gender or geographical setting.

Despite her constraints, Ellen was a valued member of a specialist botanical community, made significant scientific contributions and highlighted the importance of science communication. Ellen continues to be a role model that all researchers might wish to emulate; it is very appropriate that one of UCC’s leading research buildings should be named in her honour.

UCC has named its Environmental Research Institute building after Ellen Hutchins.

Dr Paul Bolger is manager of the Environmental Research Institute at UCC. Madeline Hutchins is the great, great grandniece of Ellen Hutchins, researcher on Ellen, and an organiser of the Ellen Hutchins Festival.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ