Mr Hoo by John O'Donnell has been announced as the winner of the RTÉ Short Story Competition shortlist 2023 – read John's story below, and hear it read by actor Emmet Farrell above.

About the story: "Mr Hoo is loosely based on a real case," John says. "I still remember the late Professor Nial Osborough recounting the grisly facts to us in First Year Criminal Law. As a kid, the need to belong is overpowering; you'll do nothing your parents ask of you, but you’ll do anything for your friends."

One says, 'Do you want to tell us why you did it, Bird?'

I fold my wings over my head. The African grey can speak hundreds of words, did you know that? But it doesn't understand what it's saying; it's just repeating the sounds it thinks people want to hear.

The other one sighs. 'Come on, Robert,' he says, and I scowl. My father's name.

Mam starts stroking the back of my neck, which makes me want to cry. 'It's alright,' she says, 'take your time. ' She pulls out a bar of chocolate, breaks off a piece and pushes it towards me. I pick it up and pop it in my beak. Did you know that flamingos can only eat when their heads are upside down? '

Mr Hoo,' I say, looking up at the two of them, and at Mam, 'where's Mr Hoo?'

The estate where Mam and I live is named after a dead poet, though I bet he never wrote a poem about here. The houses are like Rubik's cubes except all the squares are brown. But if you run past the row of mean-faced shops, past the bus-stop for the bus that hardly ever comes, past Lock-Up Lane, you come out on to the old road that now curves upwards into the new flyover. That summer there was a steel fence across the entrance because they hadn't quite finished building it, but at one end there was a gap which we could squeeze through, Yaz and Scar and me. Up there on the overpass we could look down on a world we hadn't made and feel like kings. We'd stretch our sunburnt arms along the parapet and lay our cheeks against the stone, loving its white coolness. Then we'd hoick up bogeys and gob on the toy cars passing below. All there was on either side was road, for miles and miles. Yaz claimed he could even see the ocean, so Scar and I shielded our eyes and said we could see it too. Yaz's skin is brown and smooth, his hair is black and wavy, and his dad's dead. He wears a leather lace around his neck with a ring on it that's too big for his fingers, a laughing silver skull.

And Scar doesn't actually have a scar. His real name's Oscar, and his hair's a big bright orange scribble like a bird's nest, although some birds don't build nests at all, like cuckoos.

'If you were a proper bird,' Scar said to me one afternoon, 'you could just take off. '

'I am a proper bird,' I said, and I climbed up on the parapet and spread my wings, flap-flap, the way I'd seen them do on television, and on Google. Except where we live, there aren't any birds. There aren't even trees, and though the council keep promising to plant things, Mam says you couldn't believe the Our Father out of that lot.

When I waved my arms Scar laughed, but Yaz just shook his head. 'Pair of saddos, you two.'

Scar glowered at me but then Yaz began to smile.

'Tell you what, Bird,' he said. 'I know a place where there's a real bird you can see. But you'll have to pay.'

A few years before, this guy came to the school. He brought a wooden box, with holes in it. We crowded around Miss Howard's desk as he opened up the lid. Inside there was this little trembling ball of fluff the colour of egg-yolk. 'So sweet,' one of the girls said. Yaz rolled his eyes. The guy lifted out the chick so we could hold it. When it came to my turn I could feel its heart going and going, all quiver and twitch, its claws fidgeting and scratching as it tried to get comfortable in my hands.

'They've been here since the dinosaurs,' the guy said.

'Like Miss Howard,' said Yaz, and this time it was Miss Howard who rolled her eyes.

'Why doesn't he just fly away?' asked a girl with bottle-glasses.

'At the moment he's too young.' The guy took the chick and lowered it back into the box. 'But when he's older, he'll grow wings.'

'If I grew wings, the first thing I'd do is fly away from here, as far as possible,' I said.

'Amen to that,' said Miss Howard under her breath.

'What's your name, son?' the guy said, and I told him.

'Well now, Robert,' he replied, 'aren't you the rare bird?'

He nodded at Miss Howard and closed the lid. There was a little fluttering inside the box.

We stood outside the last garage on the lane. The door was covered in bright foamy graffiti. Mam says it's called Lock-Up Lane because everyone who has one is in prison. 'Moolah first, Bird,' said Yaz, holding out his hand. I gave him the tenner from Mam's purse. Yaz fiddled with the padlock, slid the door up and we stepped in. So much stuff: a pair of boxing gloves. A busted sofa. A crossbow. A brassy tuba. Picture frames with no pictures in them. 'Who owns all this?' asked Scar. Yaz answered, but we couldn't hear him properly. 'Mr Who?' said Scar. And that's when I saw him. He was perched on a high shelf, a tawny rage of feathers glaring down at us from inside his world of glass. The neat, tucked beak, ears like horns, his eyes blazing bloodorange; and the terrible curved talons that could pierce a rabbit's flesh, that could rip the heart out of a young lamb. Straightaway I knew that I would never see anything more beautiful or more deadly. I lifted him down carefully and brushed the dust off his glass dome. 'I'll look after you now, Mr Hoo,' I said. I said it very quietly, so that only he and I could hear.

'Hey, Bird,' said Yaz, 'I've got an idea.'

Scar shrugged. 'Oh yeah? What?'

But Yaz wasn't looking at Scar; he was looking at me.

His soft brown eyes and big toothy grin; I could feel his breath as he whispered in my ear. I looked at Mr Hoo and then at Yaz. 'Ok,' I said. 'Ok, yeah.'

A murmuration of starlings. A mischief of magpies. A murder of crows. We pulled down the garage door and headed for the overpass.

Yaz had the crossbow slung over his shoulder, with a bag of bolts stuffed in his pocket. Scar had the tuba; it was so big he kept stumbling behind us, tripping over the enormous yellow horn as he lugged it up on to the flyover.

I was carrying Mr Hoo. He was heavier than I'd expected; maybe it was the glass, or maybe it was the base, with the little wooden tree stump he was clinging on to. 'Eagle-Owl,' the silver plate said at the bottom of the stump. The stump was fake, but Mr Hoo was real, so real that when those eyes stared at me I could feel them burning through me, and I was scared to look back.

We stood together at the parapet, Yaz and me. Yaz stuck a bolt into the crossbow and aimed it at one of the cars on the dual carriageway. He tried to fire, but the trigger jammed. Yaz took out the bolt, reloaded and tried again, but the same thing happened.

'Fuck this,' he said, tossing the crossbow aside. By now Scar had arrived and had taken out his mobile phone.

'Alright, Bird,' said Yaz, 'off you go. Go on.'

Slowly I removed the glass case. Mr Hoo's feathers ruffled slightly in the breeze. I prised his claws away from the fake stump and lifted him with both hands. 'Don't be afraid,' I whispered to him. Did you know that a hummingbird's heart beats more than twenty times a second? He gazed back at me with those fierce unblinking eyes. 'You're free,' I said, as I released him. Back into the wild, the way Yaz had said. He swooped away from us then in a silent rush of feathers, descending like a judgment on whatever prey he'd chosen. Because now Mr Hoo was free, free to go anywhere he wanted, to do whatever he wanted to do.

But when they play the video in court it looks different. Scar's phone jiggles as he's filming; you can hear the wind, and Yaz's voice as I take off the glass.

You can see me holding Mr Hoo out in front of me above the parapet, like yer man the monkey with the lion-cub in that film The Lion King. I let go, and Mr Hoo disappears. For a moment there's no sound except wind-noise, and empty air. Then from way below there's a squeal of brakes and smash of glass, and the screech of metal tearing against the concrete underpass until it suddenly stops. And a car-horn, wailing on and on and on.

With the older ones in here it's mostly girls, photos torn out of newspapers and magazines and taped up on the walls of their cells. For others it's cars, sports cars and racing cars, all sleek and gleaming. One boy has horses, dozens of them, blacks and chestnuts and greys, standing alone out in green fields or galloping in herds across the plains. Did you know that in America one prisoner was allowed to breed canaries? I did ask Alan about getting something small, maybe even a budgie, but he just laughed and told me to cop myself on. 'Sure, it's already like an aviary in here,' he said, looking around at all the pictures I'd stuck up in my cell. Alan's one of the care officers. We're not supposed to call them 'cells', we're supposed to call them 'bedrooms'. And this isn't prison; it's juvenile detention. There's a school, and a gym, and sports pitches. Scar would like it here, and maybe Yaz would too. I miss them both, especially Yaz. I was going to write to tell them all about this place, but Alan didn't think it was a good idea.

The boy with all the horses, he's allowed work in the stables. I told Mam about him. He burnt down a house with three people inside it. Except he didn't mean to. When I told Mam this, she went quiet for a moment and then she hugged me. 'You're a good boy,' she said, and she wiped her eyes.

There's a woodwork class as well. We're supposed to be making chairs and tables, but they allow us to make other things if we want to. I tried carving an owl out of a little block of wood. It didn't really look like Mr Hoo, but Alan said it wasn't bad, and that I should try making a few more of them. A parliament, it's called, a parliament of owls. Alan said that because I'm young, there's a law which means my sentence can be reviewed. 'I know it's a long way off, Bird, but keep your beak clean and you never know. '

And Mam told me that last week she woke up one morning to find two men digging holes outside our house. They were from the council, and the truck they came in was full of baby trees. Some smart-arse councillor's idea, apparently; there's going to be an election soon. The whole estate is full of them. 'Bet they disappear as soon as the election's over,' Mam said. But after she'd gone I kept thinking about those trees. Because the only thing they'll ever have to do as they grow up is stand there, while blackbirds and chaffinches and sparrows come in to land among the branches. To just stand there, all day long, their leafy outstretched arms full of songs.

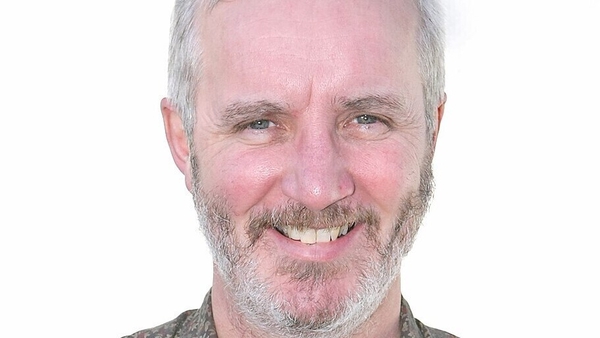

About the author: John O'Donnell is a writer and a lawyer from Dublin. Awards include the Irish National Poetry Prize, and the New Irish Writing Awards for Poetry and Fiction. He has published five poetry collections. His collection of short stories Almost the Same Blue was longlisted for the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. Rainbow Baby, a play for radio, was broadcast on RTE’s Drama On One and won a prize at the New York Festivals Radio Awards.

Mr Hoo by John O’Donnell was read on air by Emmet Farrell at 11.20pm on Wednesday 25th October, as part of Late Date on RTÉ Radio 1.

Read more stories from the shortlist on rte.ie/culture, hear updates on Arena on RTÉ Radio 1, and tune in to Arena's RTÉ Short Story Competition special which will go out live on RTÉ Radio 1 at 7pm on Friday 27 October 2023 from Pavilion Theatre, Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin, with all 10 shortlisted writers in attendance.

Judges Claire Kilroy, Ferdia MacAnna and Kathleen MacMahon will discuss the art of the short story and the stories from this year's shortlist with host Seán Rocks, there'll be live music and performances from leading actors, and we'll find out who's won the top prizes.

Why not join us in person? Audience tickets are now on sale via the Pavilion Theatre.

And for more about the RTÉ Short Story Competition in honour of Francis MacManus, go here.