David McCullagh reviews No Middle Path: The Civil War in Kerry, a new exploration of the conflict caused by the Irish Civil War of 1922–23 by historian and Kerryman Owen O'Shea,

Compared to Finland, or Russia, or Spain, the civil war in Ireland in 1922-3 was a relatively modest affair, with a death toll in the hundreds rather than the tens or hundreds of thousands.

Nor, after the opening weeks, was the outcome in doubt.

And yet, the conflict saw a level of brutality and savagery (on both sides) that left scars which have lasted a century.

Perhaps the explanation lies in the very scale of the conflict – it was fought between former friends, former comrades, in very limited geographical areas.

Great hatred, little room.

Nowhere was the hatred greater, the conflict more brutal, than in Kerry, as is detailed in this superb study, which offers an even-handed, detailed and well-written account of the war and its aftermath in the county.

While tensions had been rising for months, actual hostilities broke out on June 30th, two days after the shelling of the Four Courts in Dublin, with a pitched battle for control of Listowel, won by the anti-Treaty side. Once the battle was over, the commanding officers of the two sides issued a joint statement saying that "Ireland’s interest cannot be decided by civil war" and calling for unity.

However, just weeks later the anti-Treaty signatory to that statement, Humphrey Murphy, was singing a very different tune: "We will defend every town to the last, and you know what the result will be. You will have towns in ruins, and Ireland in ruins, and famine finishing what has escaped the bullets... we will stop at nothing in that defensive fight..."

This was not a prospect that appealed to at least some of those caught in the middle of the fighting. For example, while anti-Treaty forces mined Fenit pier so it could be destroyed if a landing was attempted, locals cut the command wire. Faced with the loss of infrastructure vital to their livelihoods, they made a clear choice in favour of economic survival.

And economic priorities were not the only ones put ahead of the fight against the Treaty. When Free State troops did land at Fenit, the local IRA were unable to warn Brigade HQ because the telephone exchange operator was busy saying the rosary rather than attending to her duties!

The landing at Fenit led to the capture of Tralee and other urban centres, and though Republicans did manage to win back a number of towns, the superior numbers and equipment of the Free State side gradually pushed them back to guerrilla warfare, for which Kerry was particularly suited.

As an Army report from the spring of 1923 put it: "It will never be possible to clear the mountainous districts of Kerry except by very cooperative movement between [army] posts. This country is so difficult and extensive that it affords excellent cover and easy retreat for the Irregulars..."

Even when the violence was over, the suffering continued.

The toll of atrocities committed by both sides makes for grim reading. The murder of the O’Connor-Scarteen brothers in their Kenmare home by the anti-Treaty IRA in September 1922 (according to O’Shea, this was partly the result of a personal dispute between Tom O’Connor-Scarteen and anti-Treaty leader John Joe Rice); the shooting dead of two off-duty Free State Army medical orderlies (who were wearing Red Cross armbands); a senior Army officer, Colonel David Neligan, beating 17-year-old republican prisoner, Bertie Murphy, and then shooting him dead after two Army officers were killed in an ambush.

There are many – far too many - stories of republican prisoners being brutally beaten or shot out of hand by their captors, usually while allegedly "attempting to escape".

The Commander-in-Chief of the Free State Army, Richard Mulcahy, worried that these unofficial reprisals were getting out of hand. Rather than imposing stricter discipline, his answer was legislation which allowed the execution of Republicans carrying arms. The Free State government vainly hoped this would make unofficial reprisals less likely. This legislation was regarded by the anti-Treaty side as a ratcheting up of the struggle, and led in turn to Liam Lynch’s notorious order to shoot TDs on sight.

The cycle of reprisal and counter-reprisal continued, embittering the struggle and poisoning Irish politics for decades to come.

The ferocious Army behaviour became much worse when Paddy O’Daly, former head of Michael Collins’ ‘Squad’, took charge of Kerry Command. O’Daly was utterly ruthless, famously saying that nobody had asked him to ‘take my kid gloves to Kerry and I didn’t take them’.

But crucially, he was fully backed by Mulcahy and by W.T. Cosgrave, who said in February 1923 that he appreciated "most heartily the very honourable action" of army officers in the country.

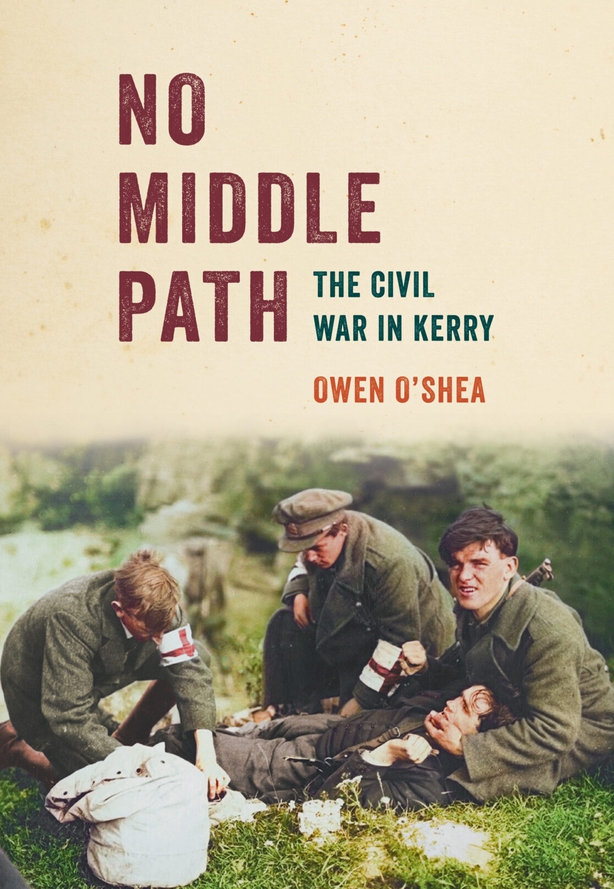

Photo: National Library of Ireland

The killings reached a crescendo in March 1923, with 39 deaths – 29 republicans and ten Free State soldiers. Among the latter were the five victims of a booby-trap mine in Knocknagoshel, which prompted some of the most notorious reprisals of the entire war.

O’Daly ordered his troops to use prisoners to clear barricades and remove suspected mines, threatening "serious disciplinary action... against any officer who endangers the lives of his men in the removal of such barricades". These were not reprisals, he insisted, but "the only alternative left us to prevent the wholesale slaughter of our men."

And that was the cover story for what happened the following day at Ballyseedy Cross, where nine republican prisoners were taken to clear a barricade. A mine exploded, killing eight of them (Stephen Fuller had a miraculous escape).

In fact, the prisoners had been chained to the barricade, and Free State troops deliberately exploded the mine – which itself was made by Army officers, on O’Daly’s instructions, according to the later testimony of another officer, Niall Harrington.

The following days saw similar atrocities at Countess Bridge and at Bahaghs near Cahersiveen.

The Secretary of the Department of Home Affairs, Henry O’Friel, was appalled, telling his Minister, Kevin O’Hggins: "There is a paramount duty on the civil authorities in the State to protect the public from military irregularities..." But Mulcahy – and Cosgrave – remained steadfast in their support of O’Daly and Kerry Command.

O’Daly was personally involved in the notorious "Kenmare case", in which two young women, the daughters of a pro-Treaty doctor in the town, were beaten up (and possibly sexually assaulted) because of a perceived slight against the Army.

Judge Advocate General Cahir Davitt wrote of this case: "One of the main reasons justifying the commencement of the Civil War was the necessity to stop unlawful interference by force with the rights of ordinary citizens... Much blood and money had been expended in putting down ‘Irregularism’; was it going to be tolerated in the Army itself?"

The answer, despite the best efforts of O’Higgins, was yes.

The Army's actions made the government deeply unpopular in Kerry – but then the economic dislocation caused by republicans in their efforts to disrupt the Free State were also extremely unpopular. Those who wrecked a recently reconstructed railway bridge were condemned by the Voice of Labour paper as "people with no end in view but a vision for the soul and a vacuum for the stomach".

Even after the formal end of the Civil War, killings continued, although at least there was punishment in some cases – one army lieutenant found guilty of the murder of a republican was subsequently hanged.

In total, 86 Free State troops died during the war in Kerry, 73 republicans (42 of them in "extrajudicial killings"), and 14 civilians – a total of 173, higher than the death toll in the county during the War of Independence, and around 10% of total Civil War casualties.

And even when the violence was over, the suffering continued. O’Shea expertly uses the Military Pension files to show how the protagonists – on both sides – were treated shabbily in later years by governments of all shades, left in terrible conditions by the independent Ireland they had fought to secure.

It is but one example of how the savage legacy of the Civil War in Kerry lived on for many years. With this even-handed, detailed and well-written account, Owen O’Shea has produced a superb account of that legacy.

No Middle Path: The Civil War in Kerry is published by Merrion Press