Opinion: how we deal with the current global challenge to food security will show how well equipped we are to tackle future catastrophes

By Eoin McLaughlin, UCC, Chris Colvin and Matthias Blum, Queen's University Belfast

Food security is a slow burning crisis. The UN Security Council was recently warned that the world only has 10 weeks of wheat left in its global inventory. The cause: droughts in major wheat growing areas of the world (such as the US), global fertiliser shortages and the Russia-Ukraine war.

The food crisis caused by Russia's invasion has exacerbated an already difficult situation. Ukraine, known as the breadbasket of Europe, is an important source of grain for human and animal consumption. In evidence to the UN Security Council, Gro Intelligence CEO Sara Menker stated that "five months have undone 20 years of progress". Russia's UN ambassador, Vasily Nebenzya, walked out of a UN Security Council meeting this week after Charles Michel, president of the European Council, said Russia was "solely responsible" for the looming food crisis.

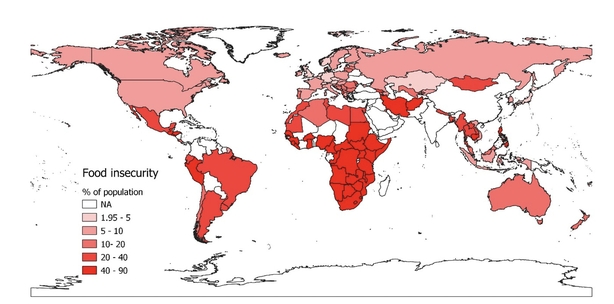

Before this, the Covid-19 pandemic worsened world hunger and one in ten of the world's population experienced food shortages in 2021. Global food prices have increased by more than half over the past two years, increasing the population vulnerable to food insecurity.

Understandably, the focus of international aid agencies right now is on the immediate humanitarian and refugee crisis caused by the Ukraine war. Aid agencies have historically been slow responders to famine disasters. Macky Sall, Senegal's president and head of the African Union, recently met with Russian president Vladimir Putin to press upon him that people in countries far from the theatre of war, 'are victims on an economic level’ because of war induced food and fertiliser shortages.

Data from FAO SDG indicators

Back-to-back global catastrophic events, such as wars and pandemics, have not happened for over 100 years. The world is slowly recovering from a pandemic and many countries are insufficiently resilient to handle war-induced food shortages. What lessons can history teach us about food crises?

Major famines in the 20th century

70 million people died because of famines in the 20th century, more than the death toll of the two world wars combined. Death tolls from famines have decreased substantially over time due to medical and technological innovations and famine mortality is now less of a risk than mortality from infectious disease Famines are no longer seen as natural disasters, but rather complex phenomena that are exacerbated by market failures. The risk of famines occurring are now seen as unintended consequences or an outcome from a hostile act.

For adequate and timely interventions, famines must first be identified. However, there is a risk of crying wolf if famines are incorrectly identified. Famine definitions can be boiled down to extreme and widespread food scarcities, or widespread life-threatening hunger.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's News At One. Simon Murtagh, senior research and policy officer with Oxfam in Ireland, on how war in Ukraine has impacted on food security and hunger in developing countries

An important distinction is identifying when food insecurity becomes a famine. The key distinguishing feature for modern famines is a rise in crude mortality as well as wasting, while historical signifiers of famine included rising grain prices, increased migration, and increased crime.

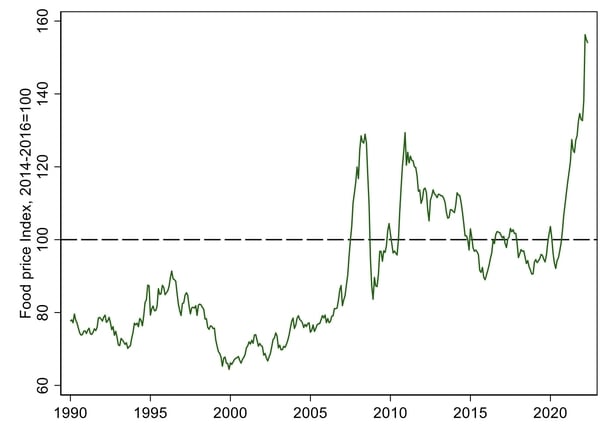

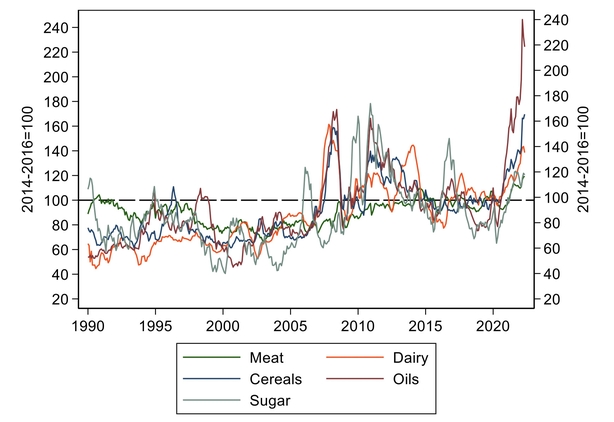

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization's food price index, a gauge of food prices around the world, hit an all-time high in March. Cereals and oils were particularly affected. The past teaches us that high food prices do not necessarily indicate famine conditions. Countries can have stores of food to rely on in times of shortage. Famines associated with back-to-back harvest failures are rare, but some of the best-known are such historical famines as the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, the Ukrainian famine of 1932-33 and the Chinese famine of 1959-61.

The likelihood of a back-to-back harvest disruption caused by war is contingent on Ukrainian farmers being able to sow and harvest crops this year. There is considerable uncertainty surrounding this. The war has led to significant delays in shipping last year’s harvest and has also impacted the quality of the crop that lays in storage as the Ukrainian power grid is damaged.

The Indian economist Amartya Sen famously identified rising food prices as a major cause of the Bengal famine of 1943. Sen set off a debate whether famines were caused by how food was distributed, or if there is a genuine decline in food availability. More recent research suggests that food availability decline can still be important even in classic cases such as Bengal during WWII.

Famine victims tend to be those dependent on others for survival. For example, mortality rates were higher amongst the young and the old during the Irish famine. Historically, many famine deaths were not due to literal starvation, but rather were from vulnerability to infectious diseases. Any severe food shortage crisis today may be exacerbated by vulnerability from the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

What are the long-run consequences of famines for those who survive? One of the most widely studied famine episodes in this regard is the 1959-61 Chinese famine. Fetal exposure to malnutrition has long-lasting impacts on physical health and cognitive development and has also been linked to second generation cognitive performance and lower lifetime wealth.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Today with Claire Byrne, how the current war in Ukraine is leading to fears of global famine

A key limitation of these studies is how to address the conflicting effects of selection (the most vulnerable die) and scarring. Taking this into account, evidence finds little scarring experienced by survivors. Our recent study of the long-run effect of the Irish Famine shows similar evidence of selection.

Preparing for the worst case scenario

Isolated cases of harvest failure can be compensated by food imports, but this is predicated on food being abundant elsewhere and shipping capabilities remaining intact. The fact that Ukraine is normally the source of abundant food used to feed the world's hungry is what makes the current situation particularly difficult.

The historical evidence suggests increasing supply elsewhere is the best way to mitigate food price inflation. For example, grain imports from the US helped alleviate some of the shortfall caused by potato harvest failure in 1840s Ireland, while many people emigrated in the other direction. Famine migrants could be the first wave of the 21st century climate refugees.

Future famine risks relate to how the world adapts to climate change. Our success at navigating the first serious global challenge to food security in the 21st century will indicate how well equipped we are to tackle multiple catastrophes in the future. We cannot just prepare for one crisis in isolation, but need to think about how crises can interact.

Dr Eoin McLaughlin is a Senior Lecturer in Economics at the Cork University Business School and an affiliated PI with the Environmental Research Institute at UCC. He is a former Irish Research Council awardee. Dr Chris Colvin is a Senior Lecturer in Economics at Queen's Management School and Co-Director of the Centre for Economic History at Queen's University Belfast. Dr Matthias Blum is an economist and policy advisor at the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer) and an Honorary Senior Lecturer Queen's University Belfast.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ