The Netherlands is already well known for a process of government formation which can take months, but the talks which lie ahead after this week's shock result for far-right politician Geert Wilders are expected to be particularly arduous.

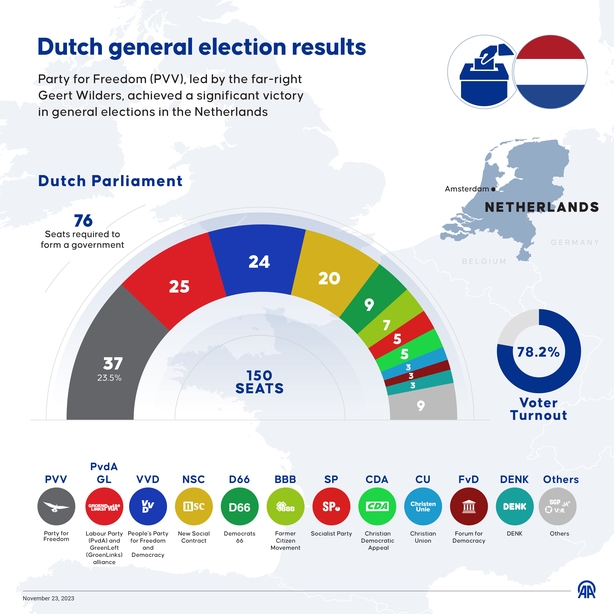

No one had predicted the outcome which saw Mr Wilders' Freedom Party gain 37 of 150 seats, and after two decades on the Dutch political scene his views on immigration, the EU and Islam are well known, leaving many more mainstream politicians wary about, if not utterly opposed to, going into government with him.

His win has left some feeling blindsided, with former European Commissioner and now leader of the left's PvdA-Groenlinks alliance Frans Timmermans telling his supporters that "now the hour has come to defend democracy".

Mr Timmermans came second in the poll and has vowed to form a "left-wing fist" to fight against exclusion and discrimination.

"It is clear that many people expect solutions from the right," Mr Timmermans said, adding that it is now up to the right to find those solutions.

Read more: Geert Wilders: the anti-Islam, anti-EU populist who could be Dutch PM

There is no certainty though that he or other party leaders will agree to sufficient sacrifices to make a coalition work.

As a political outsider for many years, there is no surprise about Mr Wilders' desire to claim a position he admits would have seemed impossible a year ago.

For many in Dutch politics it might have seemed impossible a week ago.

His supporters will also feel the weight of former outsiders who now find themselves at the centre of electoral victory.

Amid the happiness and joy they are feeling today there may very well be a fear that what they view as their electoral right could yet be taken from them.

In the wake of the UK's Brexit vote in 2016 one member of the Leave campaign told me that they could not feel comfortable about victory until they were sure they had got the Brexit they believed in.

It was, they conceded, a feeling that almost certainly came from years on the sidelines looking into a political establishment they did not believe would ever accept their views.

It may be a similar feeling for some of Mr Wilders supporters today as they wait to see what the difficult months of negotiations ahead will bring.