Analysis: The cleric and author's omission of the horrors of a Magdalene laundry for its unpaid women workers says much about Ireland's culture of incarceration

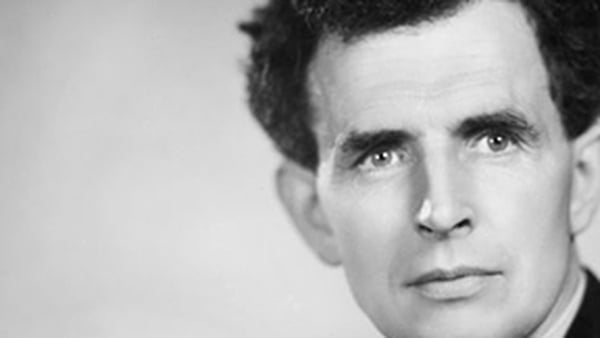

Canon Sheehan (1852-1913) was a Catholic cleric and prolific writer, who was one of Ireland’s best-selling authors, both at home and abroad. Indeed, extracts from his writings were at one stage included in the Intermediate Certificate’s set texts.

His 1901 novel, Luke Delmege, tells the story of an overly proud curate with intellectual pretensions who initially struggles to adapt to a simpler life in rural Ireland after his return from missionary work in England. Though widely read and translated into a number of European languages, Luke Delmege was criticised at the time of publication by members of the clergy for its depiction of the novel’s priest protagonist as a flawed human being.

However, in the wake of yet another report on the abuses that took place in institutions overseen by Irish religious congregations, I suspect that this novel, if still widely read, would again attract negative attention - though from a very different quarter.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Drivetime in March 2019,Della Kilroy hears from Magdalene laundry survivors as the National Museum opens a landmark exhibition in response to Ireland's 'hidden truths'

Luke Delmege contains a rare contemporary fictional depiction of a Magdalene laundry. The institution is largely taken for granted in the novel with its significance to the narrative confined to its role in the necessary development of the central character as both man and priest. Luke’s encounter with a woman who is not a 'magdalen’ but has nonetheless chosen to live amongst them, teaches him a much-needed lesson in humility.

But the fact that the novel’s portrayal of the Magdalene laundry is an untroubled one should not prevent us from "troubling" it. Luke is visiting his sister, a nun who helps run the Good Shepherd Magdalene Laundry in Limerick. He is led down a corridor, "full of flowers and fragrance," into "the first workroom." The female occupants of this room, ranging from young girls "with the remnants of rural innocence still clinging to them" to "venerable old penitents who had done their fifty years of purgatory", are "neatly dressed, and happy, if one could judge by their smiles."Yer blessin’, Feyther,’ cried one; and in a moment all were on their knees for Luke’s benediction."

The "happy" inhabitants of the laundry include Laura, whom Luke finds in the infirmary. A young "penitent" who found it hard to resist "the dread attractions of the midnight streets," Laura had been "saved" by an epileptic seizure that paralysed one side of her face. "The brand was snatched from the burning, and would never again feed the flames. Her beauty was gone." And others will be "saved" as a consequence. Laura "could never again go forth to snare the unwary with her eyes and mouth."

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Morning Ireland in November 2018, Dr Maeve O'Rourke on how the Government has undermined the State apology to the survivors of Magdalene Laundries by denying there was systematic torture at the institutions

Such disturbing passages provide insight into the mindset of those who unquestioningly accepted the existence of Magdalene laundries. However, they should not detract attention from less compelling but equally revealing details. Sheehan was in many ways a moderniser who promoted land reform, new agricultural methods, a modern housing scheme to replace labourers’ cabins and improved water and electricity systems. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that considerable attention is devoted to the technical aspects of the operation in his fictional account of a Magdalene laundry.

Upon initially entering the workroom "the awful dread that the sight of soiled womanhood creates in the Catholic mind, so used to that sweet symbol of all womanly perfection – our Blessed Lady" causes Luke to "tremble." He then sees the "seven or eight long tables, running parallel to each other" that fill the room, and the women at each table "silently occupied in laundry work" assisted by "modern appliances." No one, he reflects, could associate these "eager workers", this "happy sisterhood, working in perfect silence and discipline" with "the midnight streets, the padded cell, the dock, the jail or the river."

"The shudder that touches every pure and fastidious soul at the very name" of Magdalen had "crept over him" when he came face to face with the women. But he then realises that this is the "mechanism and perfection" that he had long sought, only that here it is correctly motivated. In this novel, Luke is not the only one in thrall to the mechanics of the workroom: the women themselves are keen to show him "the mighty secrets of the machinery; how steam was let on and shut off; how the slides worked on the rails in the drying room."

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ One's Prime Time in 2018, David McCullagh examines the responsibility of Government and the Church to accept legal liability for the legacy of the Magdalene Laundries

Of course, the reality was quite different. The machinery in the Good Shepherd Laundry on Clare Street in Limerick was often old with very few safety features. The women worked in uncomfortably hot conditions and were exposed to industrial strength chemicals. In Luke Delmege, Sheehan both omits the horrors of the Magdalene laundry and uses the unpaid labour of its inhabitants as a springboard for a celebration of modern work practices and the discipline that they can induce in those who might otherwise pose a societal risk.

In a 1975 publication, Discipline and Punish, French philosopher Michel Foucault compared the changes that had taken place in Western penal systems in the modern age with the new forms of control and containment that had developed in a range of other contemporary institutions. While the machinery in the actual Magdalene laundries may have been very different to that which Luke admires in the novel, Sheehan was right to equate the institutions with modernity.

From the workhouse to the direct provision centre, the history of incarceration in Ireland of those deemed a treat to the social and moral fabric of the country is the history of the modernisation of Ireland, albeit its dark underbelly. While it is tempting to attribute all of Ireland’s past ills to archaic beliefs, a clear-cut distinction between a modern enlightened secular Ireland and a backward benighted one in thrall to religion can mask the throughline that links the workhouse to the Magdalene laundry, the mother and baby home to the direct provision centre. One way to express our outrage at what this most recent report reveals is for each of us to ask ourselves about our own complicity in Ireland’s current practices of incarcerating those who have done no wrong, but are perceived to require institutionalisation for the "good" of society.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ